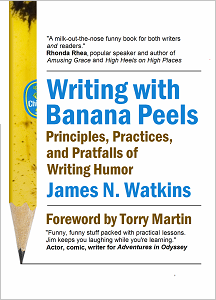

James N. Watkins

XarisCom 2009

Trade size (6×9) 132 pages

ISBN: 978-0-578-03538-3

The medical, educational, and psycho-social benefits of humor

A cheerful heart is good medicine,

but a crushed spirit dries up the bones.

Proverbs 17:22

I always wonder the reaction of parents when they discover their hard-earned money is paying for a class called “Eng 460 Writing Humor.” Maybe you’re wondering, What was I thinking when I bought a book called Writing with Banana Peels?!

Never fear! Humor is actually beneficial on several fronts:

Humor improves your health

Voltaire, a French writer and philosopher from the 1700s noted: “The art of medicine consists of keeping the patient amused while nature heals the disease.” (I keep quoting long-dead philosophers to prove that writing humor is a serious endeavor.)

More recently, Dr. Paul E. McGhee in his book Health, Healing and the Amuse System documents the health benefits of humor in:

Humor strengthens the immune system.

Laughter increases immunoglobulin A, a part of your immune system which protects you against upper respiratory problems, like colds and the flu also increases T-cells which seeks out and destroy tumor cells viruses, and foreign organisms.

Humor reduces food cravings.

(I’ll have to do more study on that as I munch on dark chocolate.)

Humor reduces pain and increases one’s threshold for pain.

Norman Cousins’ book, Anatomy of an Illness documents how a spinal disease left him in almost constant pain. He discovered that moving out of a dreary hospital and into a cheery hotel room, where he watched “Candid Camera” and comedy films, eased his pain. He specifically denied that humor “cured” anything, and repeatedly reminded his readers that he took all the medications, along with high doses of vitamin C, prescribed by his doctors.

But he did claim in his last book, Head First: The Biology of Hope, that ten minutes of belly laughter gave him two hours of pain-free sleep.

Over a dozen studies have now documented that humor does have the power to reduce pain in many patients. One study surveyed thirty-five patients in a rehabilitation hospital suffering from such conditions as traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, arthritis, limb amputations, and a range of other neurological or musculoskeletal disorders. Nearly three-fourths (74 percent) agreed with the statement, “Sometimes laughing works as well as a pain pill.”

The most commonly given explanation is that laughter causes the production of endorphins, one of the body’s natural pain killers. However, medical kill-joys point out that only two scientific studies have been conducted on this claim, and each failed to show any increase in endorphins.

In June 2008, Basil Hugh Hall addressed this in his paper “Laughter as a displacement activity: the implications for humor theory.” While he states that laughter does not produce endorphins, he writes, “However, recent advances in imaging techniques have enabled researchers to demonstrate an increase in opioids in the brain after strenuous exercise (Boecker et al 2008), and there is no reason to dismiss the idea that a similar increase in the brain’s opioids will be found after a laughter evoking event.” (So, please, don’t submit to a drug test while reading this book!)

Humor reduces level of stress hormones such as cortisol, epinephrine (adrenaline), dopamine, and growth hormone.

Humor is a cardio-vascular workout.

Some have called laughter “internal jogging” which may reduce blood pressure. There’s even an emerging therapeutic field known as “humor therapy.”

Humor improves communication

This is why I’m glad Taylor has included “Writing Humor” in it’s professional writing program. Humor improves communication in all disciplines.

I actually wrote a paper in graduate school called, “Effectiveness of the Use of Humor on Persuasive Messages in Print.” It used university studies to document that. . .

Humor attracts attention in all types of persuasive messages in advertising, politics, debating with your seventeen-year-old daughter.

Humor increases likeability of the source, but doesn’t necessarily enhance source credibility. (People love clowns, but don’t elect them to office. Okay, bad example.)

Humor doubles persuasiveness of a message. According to a 1990 study by Biel and Brigwater, individuals who liked an advertisement were twice as likely to be persuaded to act upon it.

Humor increases comprehension in education.

In 1990, Gortham and Christophel set up an experiment in “Introduction to Statistics” classes. (Now there’s a coma-inducing subject!) Two classes were taught by the same professor using the same text and syllabus, but in one class relevant humor was used and the other class included no humor.

I’m not exactly sure what “statistical humor” involves.

“Two binary variables walk into a bar. . . .”

“What did the hetereoscedastic data say to the homoscedastic data?”

“How many dummy variables does it take to screw in a light bulb?”

But I digresss. Researchers found that in the class using humor, students scored 10 percent higher than their counterparts!

Humor causes listeners/readers to lower their defenses.

Think of humor as “laughing gas” that allows you to drill away at sensitive subjects as we’ll see later.

Humor makes you smarter

James Lyttle also claims, “The creation and appreciation of humor has long been associated with high intelligence, problem solving, creativity, generativity, and high verbal ability. Humor involves the suspension of the normal rules of logic, as does innovation and has been shown to enhance mental rotation.”

I have no idea what “mental rotation” is, but I suddenly feel so much better about being a humor writer. You and I are highly intelligent people that surpass the normal rules of logic! (And you thought you were just the class clown!)

However, I think I just pulled a hemisphere just writing about the psychological and neurological aspects of humor. (If you want to explore more, visit Dr. Lyttle’s fascinating site www.jimlyttle.com/Humor.html and www.humorlinks.com.)

Humor connects with readers

Using humor then, literally creates good feelings in our readers and listeners. Equally powerful in humor, is the awareness of, “I’ve felt that same way” or “That happens to my family all the time.” The best sitcoms and standup routines are funny because we see ourselves—or more often others—in the humorous situation.

It brings a sense of connection. We have something in common, even if it only is our eccentric uncles. I’ll provide several examples of connecting comedy in chapter x.

Humor comforts our readers

Best-selling humorist Barbara Johnson is a prime example of the concept “comedy is tragedy plus time.” Someday we’re going to laugh about it! Barbara has experienced more pain and loss than most spouses or parents, and yet she is able to write with wit and warm that comforts her readers.

Erma Bombeck would agree. “Laughter rises out of tragedy, when you need it the most, and rewards you for your courage.”

So, our shared experience, told in a witty rather than whining manner, comforts. The apostle Paul writes: “We can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves have received from God

(2 Corinthians 1:1-4).

Here’s a column that came out of extreme pain, but continues to comfort readers:

Everyone needs to have a kidney stone once in his or her life time; preferably, the sooner the better.

You see, experiencing the sensation of having a semi tractor-trailer with snow chains and a load of rolled steel park on your lower back tends to put life into perspective.

For instance, if you’re riding in a tour bus and the rest room door suddenly swings open and you can’t reach the handle without creating an additional sight on the tour, you can say, “Hey, sure beats a kidney stone.” (All of these examples are, of course, hypo-thetical and have never happened to me personally.) Or your daughter calls you at 1 AM in the middle of winter and says, “Uh, Dad, did you know that a ’95 Neon can straddle a traffic island?” you can say, “Hey, sure beats a kidney stone.”

This perspective also works for times you attempt to repair the toilet yourself and manage to not only cripple the commode, but break off the main water shut-off valve. (I did mention that these are strictly hypothetical examples, didn’t I?) It helps when your mother-in-law backs into your brand-new car. The time your five-year-old son drives spikes into your coffee table. When you lose a great job as an editor at a publishing house due to corporate down-sizing. While you’re recovering from double-hernia surgery and something on TV prompts a belly laugh. When you’re spending half your vacation time sitting in a traffic jam in downtown Chicago with a stick shift, no air-conditioning, and two kids in the back seat waging a fight to the death. You can always say, “Hey, sure beats a kidney stone.”

It also works for intestinal flu, crashed computers, lactose intolerance, sadistic dental hygienists, arthritis, overdrawn checking accounts, terminal toasters and transmissions, impacted wisdom teeth extractions, prostate exams, IRS audits, and flat tires in the rain fifty miles from any form of civilization. Now there are some things that are worse than a kidney stone such as death, divorce, and “Saved By the Bell” reruns, but most domestic disasters and occupational pratfalls pale in comparison to a kidney stone. And that puts everything in perfect perspective.

It’s been six years since my painful epiphany, which brings me to another kidney stone insight: “All things must pass.”

Copyright © 1997 James N. Watkins

Humor confronts our readers

I wrote earlier that German philosopher Arthur Schopenhaur claimed that laughter is the “sudden perception of incongruity” between our ideals and our behavior.

When I was at Ball State for a graduate classes, one of the students kept arguing “Well, you know,

there are no absolutes.” I finally got so tired of that argument, that I wrote this column:

Are you absolutely sure there are no absolutes?

A while ago, David Samuels wrote in New York Times magazine—and I quote—”It is a shared if unspoken premise of the world that most of us inhabit that absolutes do not exist and that people who claim to have found them are crazy.”

Being the “crazy” person that I am, I honestly don’t understand the following tenants of the truly tolerant like Mr. Samuels.

“There is no such thing as absolute truth.”

Help me understand this. You’re saying it’s absolutely true that there’s no absolute truth. And if that’s true, how can you be sure your statement is truth?

“I only believe what I can perceive with my five senses.”

Hmmm? Can you prove that statement by sight, smell, hearing, touch, or taste? I don’t think so.

“What is right and wrong are for the individual to decide.”

Okay, so rapper R. Kelly, who allegedly had child pornography on his computer, shouldn’t be harassed by intolerant authorities because pictures of naked 12-year-olds are “right” for him? And that wacky Iraqi, Saddam Hussein, is simply expressing his individuality by using chemical weapons on his own people and taking his sons out for a night of torturing political prisoners.

Aren’t there some things that are always wrong for everyone? And if you say “yes,” aren’t you admitting to a “moral absolute”? If you say “no,” I’m assuming it’s okay with you if I steal your wallet.

“Well, right and wrong is what a society decides it is.”

Hmmm? So slavery was right for thousands of years until society recently decided it wasn’t? How about segregation? Was that just fine until a majority in Congress decided it wasn’t in 1964? And why are we hassling societies of China, North Korea, and Sudan for the torture and murder of religious minorities?

“No, something is wrong if it hurts other people.”

Wait a minute. I thought you said there were no moral absolutes? Is that always true for all cultures? Aren’t suicide bombers in the Middle East idolized as moral heroes by a part of society?

And how ’bout the person in a mask who comes up to you, knocks you unconscious, slashes open your chest, and takes all your money? Of course I’m talking about a cardiologist. So, isn’t some pain good for us? Isn’t “hurt” an absolute concept? And what about sado-masochism?

“Well, you shouldn’t try to change other people’s beliefs.”

But what if I disagree with that statement? Aren’t you trying to change my beliefs?

Let me get this straight, it’s “right” for you to try to convince me of your ideas about “no absolute truth” and “individual morality,” but it’s “wrong” for me to try to take my beliefs out into the arena of public debate?

“You’re just intolerant!

So, you’re saying I’m intolerant for simply voicing my beliefs, but you’re “tolerant” for rejecting my views as “intolerant”?

Hmmm? Are you absolutely sure about that?!

Copyright © 2003 James N. Watkins

So tell your parents or spouse, by taking this class and buying this book, you’ll actually be healthier and actually cut medical expenses, be a more persuasive person, a better teacher, a more compassionate person . . .